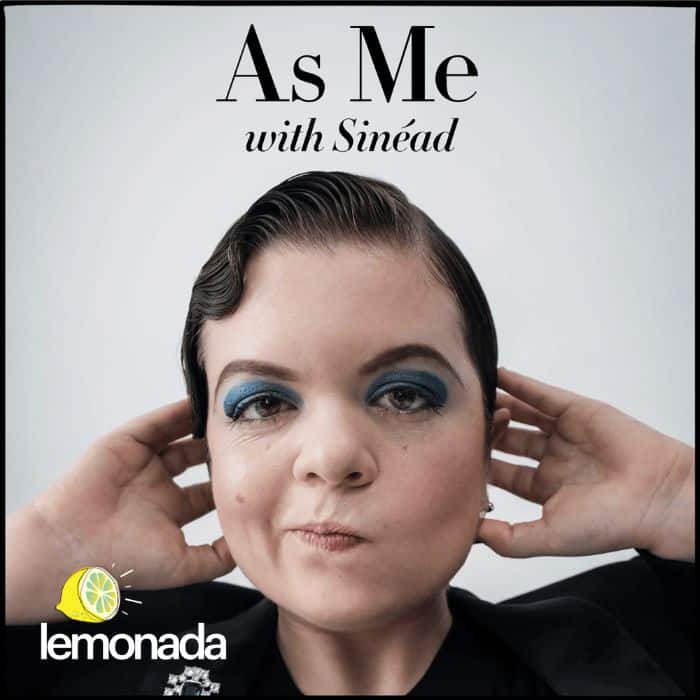

As Me with Sinéad — 8: Glenda Jackson

Subscribe to Lemonada Premium for Bonus Content

As Me with Sinéad — Glenda Jackson transcript

[00:56] Sinéad Burke: Welcome to As Me with Sinéad. I had the privilege of traveling to New York a little while ago. Actually, I was in town to attend the Met Gala, which is a weird sentence to be able to say. And the person who was sitting across me in the studio was also attending the Met Gala. It was our collective first time to be there. It was with the extraordinary Glenda Jackson, who had just played the male lead in her 80s in a Broadway production of King Lear. Talk about breaking boundaries. We chatted about so many things, including her winding, undulating career, both in theater and the British parliament. Yes. Yes, you heard that correctly. And what it’s like to be in her body today as an octogenarian hero.

[01:43] Glenda Jackson: The envelope that carries that inside me around is increasingly disobedient. You know, my fingers won’t do what I tell them to do. Or my knees aren’t as flexible as I would like them to be. And the other major thing that I’ve learned is how little I know — or rather the obverse of that, how much I don’t know. And that’s come as a big surprise, actually.

[02:07] Sinéad Burke: What’s on my mind this week is the power of one individual. When we talk about climate change, and seeing all that needs to take place to ensure that our world is sustainable and protected from the actions that we have done so recklessly for such a long time. I don’t know about you, but I’ve been feeling overwhelmed. It just seems that there is so much work to do, and so little time, and so little political interest in doing so. But I’ve learned anything this year, it’s that one person can make a huge difference. And being inspired by somebody like Greta, who has rallied children from all over the world to step up and take action. It really makes me constantly ask myself, what can I do? And wouldn’t the world be a better place if we all asked ourselves that question at least once every day? Are you ready for this week’s episode? Let’s go!

[03:06] Sinéad Burke: Welcome to As Me with Sinéad. I have the great privilege and honor to be sitting opposite the extraordinary Glenda Jackson. Glenda, I must tell you that when I spoke to my parents at home in Ireland — my father’s British and my mother’s Irish. When I was telling them about As Me and that you would be one of my first guests, they exhibited enthusiasm that I have not seen for my career in quite a lot of time. So I was — they were sending congratulations and incredibly well-wishing texts from home in Ireland.

[03:40] Glenda Jackson: Well, how very kind of them. Thank them for me if you would.

[03:42] Sinéad Burke: I will. Of course. But I suppose lots of different people from different generations know you based on your career in so many different ways. Be it from politics, or be it from theater and film and television and acting. But how do you define yourself both personally and professionally?

[03:59] Glenda Jackson: Well, I find it surprising that you say that I’m sort of well-known. I mean, yes, I’m old, I’ve lived a long time. But one of the remarkable benefits really in a sense is I can go anywhere and nobody bothers me. Because nobody recognizes me. And that’s a big treat. Partly, I think, because of the length of time I’ve been around. But also the great benefit of England — being not London-born, but living there — is that you are allowed to do your job and go home. You know what I mean? I mean, people aren’t really that interested unless you’re a pop star or something like that. And as I’m markedly not. How would I define myself? Well, one of the truly interesting things I found about getting to this age is the inside you — my inside me — is round about 15 or 16, which I have to say was one of the worst times of my life. But I now have the experience of knowing it does get better. But the envelope that carries that inside me around is increasing disobedient. You know, my fingers won’t do what I tell them to do. Or my knees aren’t as flexible as I would like them to be. And the other major thing that I’ve learned is how little I know — or rather the obverse of that, how much I don’t know. And that’s come as a big surprise, actually.

[05:25] Sinéad Burke: That piece about your body being disobedient to your own self. I can relate in some ways in terms of comparing my own physicality, in that I’m a little person, to everybody else’s. And there is a societal expectation that my body should do the same things as everybody else. But for genetic reasons, it’s just not possible. But have you had to adapt yourself in terms of getting to this new place and being frustrated with your own body?

[05:52] Glenda Jackson: The biggest thing I’ve had to adapt to, in a way, is that my balance has gone. I mean, I woke up one night to go to the loo, I think was three o’clock in the morning, and I was totally incapable of walking a straight line. And of course, my family panicked and they rushed me to a hospital the next morning. And I had all the tests and things. They thought I’d had a stroke or something. And I hadn’t. I mean, simply that my balance is gone. And I do have a set of exercises to try and restore my balance. But why now? Why this minute? You know, I mean, one minute you can walk absolutely straight and the next minute you’re banging into things. But there are positive sides I think of age and things like that. I mean, I am quite — well, ruthless isn’t the right word. I will play the old person card if I think it’s going to be to my benefit. You know what I mean? Which is pretty shaming. I have to say. The first time a young person stood up and offered me a seat on the tube in London, I was outraged. I’m now very grateful that they do.

[06:54] Sinéad Burke: I come across this exact same. You know, there are particular seats, as you said, on the tube in London where people say, you know, stand up if you see somebody in need. And this dialog then happens because people are — don’t want to offend me by offering me a seat in case they think they’re othering me in some way, though, it can be quite vulnerable making of yourself to approach somebody and say, I’m really sorry, but would you mind stepping up for me? And it’s how do we as a society get better at that? Do people just need to ask? What’s the best kind of process?

[07:24] Glenda Jackson: I wish I had an answer to that, but I’ll give you an example which simply makes the question more complex. My daughter-in-law was coming home from work on the surface train in London. It was the rush hour. It was very, very crowded. There was this mother with a baby and no seat. And there was a guy sitting on the end seat. You know what they’re like on the surface trains in London. And she said to him, I need to feed the baby. May I sit there? And he said, no. Work that one out.

[07:56] Sinéad Burke: Some people are just not so nice as individuals.

[07:58] Glenda Jackson: Indeed. And that reflects on us. I mean, I don’t mean us necessarily as individuals. Certainly in some kind of community situation, which is traveling on public transport, isn’t it, in the rush hour. It is quite interesting.

[08:13] Sinéad Burke: But I also think it’s how we frame it societally. You know, we are now inventing all of these things — like people wearing badges and saying, you know, baby on board, or I need a seat. And it’s kind of further highlighting and amplifying those who have challenges or needs or disabilities. Why don’t we put the onus on those who are able-bodied to say, I’m willing to stand up for you. Like, I am a nice person. Why are we not marketing the kindness of people?

[08:38] Glenda Jackson: Well, I think we do in a sense. I mean, certainly I’m looking at London’s public transport. And as you’ve already said, there are certain seats that are designated for special use for people who have difficulty in standing and things of that nature. It’s very complicated because it’s partly this thing of we now are in a world where communication is via machine all the time. I mean, we’re communicating to other people via machine, but it’s something we both know quite well. It’s called radio in my country is called wireless. Although I now realize here in America the wireless means artificial intelligence as well. Anyway, I put that to one side. But we all see it all the time. People who are constantly on their telephones, walking down the street, looking at their computers, things of that nature. And the thing that worries me quite a bit is are we eventually going to lose the capacity to actually look each other in the eye and have a conversation? And you’ve touched on it by saying, why can’t we express our kindness more openly? In times of great drama, great tragedy, we do. And I find that, you know, really heartening. We are still all human beings, actually. But this direct communication is simply going to get more and more distant because we only think about machines.

[09:58] Sinéad Burke: And only think about ourselves as individuals within that process. But dissecting London’s transport system is not initially where I thought we would begin this conversation. But I’m so glad that that’s where we have started. But I wanted to ask you, can you remember your earliest memory?

[10:15] Glenda Jackson: I’m not absolutely certain whether I remember it, or it was what my relations at the time told me was the case. When I was 18 months old, I had, I think, severe bronchitis. And I was staying at the time with my maternal grandmother. And when I stayed with her, I had a cot in her kitchen by the then-coal fire. And an aunt had given me a duck which was clothed in velveteen diamond shapes. A pretty duck. And I remember that quite distinctly. But whether that’s me or it’s whether I was told that story so many times by relations, I’m not absolutely certain.

[11:00] Sinéad Burke: And did that duck cover a long life within yourself?

[11:04] Glenda Jackson: Oh, it did, yes. Because my first sister — I was the eldest of four — didn’t arrive until I was four years old. And so, yes, I still had the duck, I think.

[11:16] Sinéad Burke: I’m the eldest, too. But I’m the eldest of five. I have three sisters and one brother. Being the eldest is tough.

[11:22] Glenda Jackson: I accused my mother — much to her shock — this accusation took place when I was well and truly grown up — and I said to her, you gave me far too early in my life, a far too large sense of responsibility. Because, of course, wherever I went, my sisters had to go with me. I mean, no question, no choice on my part. If I was going somewhere, they had to go with me. She was quite shocked by that, I think.

[11:47] Sinéad Burke: Do you think it stood you in good stead growing up?

[11:50] Glenda Jackson: I don’t know whether the responsibility stood me in good stead. What certainly stood me in good stead, and for which I’m intensely grateful, is I come from what we used to call the working class. I think it’s got some other socio-economic definition now. And it was very simple, actually. If you didn’t work, you didn’t eat. And so I have a very, very strong work ethic and I’m very, very grateful for that.

[12:15] Sinéad Burke: Neither of my parents went to university or went to college. I was the first within my family in which to do so. But my parents understood that education was a catalyst for a societal change. And like that, perhaps transitioning through socio-economic classes and exactly that. My parents used to sit with us every evening and read stories to us because they understood the importance of literacy, or doing our spelling test with us on a Thursday night before going into school on a Friday. And exactly as you said, putting in those principles and building, I think, a moral compass for individuals is so fundamental.

[12:49] Glenda Jackson: Oh, it is. And I think it’s one of the ways that we — we’ve started early talking about not being in touch. But it is one of the things that keeps in touch, isn’t it? Because it’s a harsh lesson to learn, but it is an absolute truth. Human nature is immutable. We don’t change. I mean, hopefully the human condition can be improved. And certainly we’ve seen that around the world. But that acceptance, regardless of our external envelope, we are the same — is something that is absolutely vital, I think, for everything, in truth. And I sometimes wonder whether it’s beginning to fray bit round the edges. I mean, I was just thinking back to when the Second World War was on. And American troops billeted in our street — on the other side of the street where we lived. But nonetheless. And when the VE Day celebrations took place, which was a street party, these guys absolutely raided their PX on their base with these cans and cans and cartons, enormous cans of ice cream. I don’t think the kids liked it because we’d never tasted it. But, you know, the adults certainly made up for our lack. But those guys would send care packages to our street, to virtually every house, for almost two years. I mean, I can still remember the fights my sister and I would have because always in the care package, there would be a tin of fruit cocktail. And my mother would meticulously measure out how much cherries were in each dish because they were the big thing. And my sister and I would count to make sure that we had equal number of cherries in our dish of fruit cocktail. And America is, as you know, across the world, you see examples of huge compassion and generosity to other human beings. But it’s on the — as you pointed out — it’s on that direct, face-to-face individual meeting individual. You seem to be losing all sense of who we are.

[14:47] Sinéad Burke: But I think it’s about making sure that that compassion is rhythmic. And by that, I mean it is often reactionary, as you have just said, that when an incident happens, we are overwhelmed by that moment and respond with such emotion. But often there is a time that lapses then in which we become reconditioned by a system. So how do we change in a sustainable way?

[15:11] Glenda Jackson: Well, speak I mean, I would speak here politically from a dimension there by defining that in perhaps different ways. I mean, the obvious way is taxation. I believe in the egalitarian societies. You put forward that argument of regarding taxes as being of benefit to everybody and you get very scathing responses. But not exclusively though. The idea of how in a sense what we’re talking about here is how you create a functioning society, isn’t it? And we have to be, I think, rather more imaginative in how we define what constitutes that society.

[15:49] Sinéad Burke: And also in our ambition, we have to be as aspirational as possible. But you mentioned there your time —

[15:55] Glenda Jackson: Well, aspirational for that society. I mean, I think we are aspirational, but perhaps too often it is singular. It’s our own aspirations. It’s seen as what we as individuals achieve, when in fact, of course, the real aspiration should be of how we can be aspirational for each other as well as for ourselves.

[16:22] Sinéad Burke: And I think the increasing diversity of different types of voices that get to participate in that conversation of what a society should look like in turn will evolve and something that’s a bit more fairer and just for everybody.

[16:34] Glenda Jackson: You should get off the idea of what it should look like, but rather more into what does it feel like. And I think that way, yeah.

[16:42] Sinéad Burke: And you you mentioned there about your time in politics. One of the things that strikes me most from your career is the fact that you have such a strong voice and sense of it, either as an actress, an actor, or either as a politician. But I really wanted to know and to learn from you were you very cognizant and conscious growing up of having something to say? Feeling like there was injustices or there was an importance for you to step forward and to be an advocate? Or was it much more organic in that way?

[17:12] Glenda Jackson: I think it happened. I had no great sense of purpose, really. I mean, I left school with no particular qualifications. I was fortunate enough in those days, if you go to places I did as a drama school, your local authority paid for it. But those days are gone. That was interesting going through that process of being in a vastly overcrowded profession, virtually never being employed, until the point where you were being employed. But that sense of there being something that one could do within that kind of structure, which for me was a political party, I think came rather late down the road. But nonetheless, I’m very glad that it did. I’d always supported the Labor Party when I was old enough to vote. Just a little sidetrack — when I was an MP, you’d have all these school kids, you know, who would come in and you’d answer questions. And a recurring question always for secondary school pupils was why can’t we vote at 16 as opposed to 18? We can join the army. We can get married. We have to pay taxes. My response always was, from my point of view, because you don’t vote when you are 18. It would be interesting to see in the future if they will vote when they’re 18. But that sense of the possibility of us all working together to create a kind of society in which everyone can function to their best capacity came rather late in the day. But I’m grateful that it did. And I’m grateful that I was afforded the opportunity. Not so much — well, yes, I mean, it is a privilege to sit in the Chamber of the House of Commons and all that kind of thing. But the real privilege is representing your constituents in — as I was lucky enough to be elected for a constituency. And it is a true privilege. And very, you know, as an MP, you hold advice surgeries. And people would come in, never seen before in my life, didn’t know them, they didn’t know me. And they laid their life out on the table in front of you because you, as the member of Parliament, were the port of last resort. And not infrequently their lives were terrible, through no fault of the individuals. And the truly humbling thing — whether you got the result they wanted or whether you didn’t — they all invariably said thank you. And you think, yeah. You’ve given me — well for me, they’ve given me that great, great gift. Their vote. Not a gift, their right. That they put their cross next to your name, your party. And they always said thank you.

[19:51] Sinéad Burke: Why do you think they put that cross beside your name and your party?

[19:55] Glenda Jackson: Well, there were people like me who will always vote Labor, always vote conservative, always vote Lib Dem, always vote whichever party they’re associated with. There are those who actually read the party manifestos and their principles. Not, you know, 100 percent, but nonetheless, there is a community of purpose there. For others, it’s the first time and they just want to vote. And I’m not saying, you know, it’s the first alphabetical letter they recognize that promotes their vote. Not that at all. But what was really, really interesting to me was over the Brexit referendum, that vote. It was the largest turnout of voters ever recorded in my country. Be it local elections, which are always fairly small, the turnout. To general elections. And that came as big a shock to me as the actual result. I’m still trying to get my head ‘round it.

[19:51] Sinéad Burke: Well, I come from Ireland and we had two very large extraordinary referendums in recent history where we’ve had a huge number of people going to the polls. And again, the power of that voice — and I think particularly within my instance, you know, the power of that young people’s voice and the power of also individuals — our two most recent referendums were about marriage equality and a woman’s right to choose.

[21:19] Glenda Jackson: I know. Absolutely fantastic. Wonderful results.

[21:23] Sinéad Burke: But change came about not just because of political lead, but due to the agency of individuals who were sitting with family and friends and explaining some of the most difficult or vulnerable or emotional parts of their lives. Whether that was coming out, whether that was an abortion that they’d had to have in their youth. And exactly as we’ve been talking about building that human connection and saying this isn’t just about politics. This isn’t just about left or right, conservative or liberal. This is about people. And I think so often when we talk about politics, sometimes we forget that this is about people.

[22:02] Glenda Jackson: Absolutely, absolutely. Because there is that thing — even though I’ve been very critical of artificial intelligence and social media and that kind of thing in the early part of our conversation. Nonetheless, I am convinced that social media has had an influence on these kind of fundamental changes in our societies. Because it’s meant — I mean, I go back to when I was much, much younger than I am now. And I can remember there seemed suddenly to be a flood of writings, of books, of communication in that day without social media in that way, actually arguing that women had a second-rate definition, as far as the world was concerned. And that whole idea of being less than men suddenly took on, as far as I was concerned, the realization that I wasn’t alone in feeling that. And up to that point, I had thought I was the only person and I was, you know, just too big for my own boots, as my area of the world would put it. And so those kinds of fundamental realities, which we are not alone in what we’re feeling, we’re not alone in what we’re experiencing. And that it can produce profound, profound and fundamentally basic, good changes in our society is a great treasure. Even though I’m very critical, I mean, of how social media can be misused, but then we can misuse everything. But on its positive side, it’s just amazing.

[23:40] Sinéad Burke: Well, I genuinely wouldn’t be sitting across from you today without the Internet. My background is in education — I’m a primary school and elementary school teacher. And in many ways, I foresaw that to be my career for 60, 70, perhaps 80 years, until I retired. Whatever age that will be. And I became really interested in fashion because I felt left out, because when I walked through a store, I couldn’t reach the rails. I couldn’t find clothes. I couldn’t see myself in any of the campaigns. So I started using social media and the Internet as a vehicle to tell those stories. And that has transformed my life. And now getting to do something like this with As Me with yourself is incredibly — but exactly as you said, it’s not always the technology, it’s how you use it. But you spoke there about the importance of visibility, which really brings me on to the project that you’re currently working on. And as an advocate, and as somebody who is disabled and a minority in so many ways, there is that phrase, if you can see it, you can be it. And I have lived all of my life wanting to see stories, or art galleries, or museums, or institutions exhibiting my experience and a reflection of that. It has rarely happened. And yet here you are on Broadway in a Shakespeare production, playing a role that many people perhaps couldn’t even conceive of some time ago.

[25:00] Glenda Jackson: Well, I have a great friend, a wonderful Spanish actress, Núria Espert, and she did King Lear in Barcelona. And I went over to see her. And she was just marvelous. It was a wonderful production. And she said to me, why don’t you do it? And I said, don’t be ridiculous. I’d stopped being an MP by them. I said they would never let me play Lear in England, come on. Anyway, I come home and the Old Vic wanted me to do a play. Beautiful theater. Played there before. And over a period of time when we decided it was Lear and there I was doing it. And when I was still an MP, part of one’s job was to visit old people’s homes, day centers, things of that nature. And what I found fascinating was as we grow older — as we’re all getting to live for much, much longer — those absolute boundaries which define gender begin to crack. They begin to get a bit foggy, a bit misty. And I find that very useful playing Lear. And nobody, nobody ever mentioned it to me from an audience perspective. Nobody’s ever — except a woman said to me one night waiting outside for the autographs, ‘it’s the first Lear I’ve seen where I was aware of his maternal side.’ I thought, oh, well, that’s interesting. You know what I mean? I mean, there’s an aspect there. But that is something that I saw in, you know, non-Shakespearean characters in day centers and places like that — that, yes, we do begin to give up on the gender definition of who we are or rather what defines our gender.

[26:45] Sinéad Burke: And so many people have been trying to kind of change and provoke that thought. But you spoke there very briefly about how the conversation came about in the Old Vic and then the role just happened. I would love to learn more. Was it a negotiation? What was said your suggestion?

[27:00] Glenda Jackson: Initially, the Old Vic were concerned that they were physically — they are — physically too close to the Globe Theater, which is exclusively Shakespeare. And they are, in a sense, a nonprofit organization. They have to think about profits in that way. But eventually they said, yes, okay, we’ll do it. And a director who had done the play three times before said, yes, she would do it. And there we were. One of the shocking things for me, actually, was that in the main, it was a young company. But they’d all worked. These kids had all worked. They had never worked on a theatrical stage. All their work had been for cameras, television, film, microphones. I couldn’t believe that. I couldn’t believe that they’d never been on a theatrical stage.

[27:46] Sinéad Burke: Did you feel like you were going back to your childhood and being the eldest sibling again?

[27:50] Glenda Jackson: No, do you know, I really didn’t, because there is something very remarkable — and I think we’re very fortunate those who have the privilege of experiencing in it. In the theater, you have to communicate on a level which is much deeper than the normal kind of form we’re getting, you know, people slowly — I mean that kind of thing. And you may not see somebody — I’ve had this exchange many, many times — for decades and you bump into them in the street and it’s as though you’ve both just walked out of the same coffee bar having had coffee. You know what I mean? This kind of interaction always. And walking into a theater, which I had worked in several times before, it was as though I’d never been away. A friend of mine, when I was worrying about doing it, said to me, ‘oh, come on.’ I said, ‘what if I’ve forgotten how to do it?’ She said, ‘don’t be ridiculous.’ She said, ‘it’s like riding a bicycle. You never forget how to do it.’ So there we are.

[28:49] Sinéad Burke: And were you very worried?

[28:49] Glenda Jackson: I was. I was very worried. Not so much that I’d forget how to do it, because, you know, you do it for the first time every performance. But I didn’t think I would have the physical strength, or the vocal strength, to actually do it. So I started exercising. I would walk down the hill from my house to the local swimming pool and swim.

[29:10] Sinéad Burke: And have you had to upkeep a certain kind of routine as you’ve done the performance?

[29:14] Glenda Jackson: I haven’t kept up that routine, but I do have a very kind of — my working day starts at two o’clock. The curtain doesn’t go up until seven, but from two o’clock on, there’s nothing other than that.

[29:27] Sinéad Burke: And within the performance and the play, what’s been the most challenging moment?

[29:34] Glenda Jackson: Well, the most challenging moment is walking onto the stage. Because as I said, every performance for me is the first time I’ve done it. I’ll give you a precise example of what I mean. I worked — I did a lovely play called ‘Stevie,’ which was about the poet Stevie Smith. And the marvelous, marvelous actress called Mona Washbourne played my aunt. And we would sit on the stage waiting for the curtain to go up every performance. And she had been the product of a theatrical family. I think she’d been working in the theater acting since she was about seven or eight. She was highly regarded, marvelous actress. And she sat there on this sofa in her 70s, every performance, and she’d say, ‘Please, God, let me die. Please, God, let me die.’ And the curtain went up and she was fine.

[30:25] Sinéad Burke: She didn’t. She survived.

[30:28] Glenda Jackson: She didn’t die. She just kick the ball out of the bar.

[30:30] Sinéad Burke: And being involved in politics and stepping forth and being a voice — not just for yourself, but for your constituents — there is so many opportunities in which you can be criticized quite publicly and quite vocally. Has that — and being a politician and that experience of criticism — helped with acting or are they different entities?

[30:50] Glenda Jackson: Oh, I think they’re rather different entities. The one benefit that I had was, years ago, I remember reading a report here in New York that had studied what we as human beings fear most. And after death, public speaking is the thing we fear most. And for me, that wasn’t a problem. I could, you know, stand up, speak to a roomful of strangers, and things like that did bother me at all.

[31:16] Sinéad Burke: I’m tempted to ask you what you do fear.

[31:17] Glenda Jackson: Flying. Petrified of getting cold. Getting some minor ailment that will reduce the energy I’ve got. All those kind of practical things.

[31:29] Sinéad Burke: All the physicalitiies and pieces.

[31:31] Glenda Jackson: All the physicality.

[31:33] Sinéad Burke: And across your career, I mean, you know, you’re a parent, an advocate. You have won Oscars and Emmys and Tonys. And, you know, you —

[31:42] Glenda Jackson: Well, you don’t win them, actually. I mean, I really — they’re very nice to receive as gifts. And that’s what they are. But I mean, you’re not competing with other people in that sense when you’re acting. I mean, when you’re doing a play, for instance, everyone is responsible for the whole play, large or small. That’s everybody’s responsibility. And also in film. So I don’t regard that I won them. It’s not like, you know, running a race in the Olympics. They’re very nice. They don’t make any better. But, you know, they’re very nice to get.

[32:11] Sinéad Burke: Well, how did you feel when you got them?

[32:13] Glenda Jackson: Well, pretty much like that. I got the call with regard to the Oscars. It’s something like three o’clock in the morning. So I wasn’t in my best receptive mood. But no, I mean, they’re nice, but yeah, there you go.

[32:26] Sinéad Burke: So they don’t hold that overwhelming value for you?

[32:29] Glenda Jackson: Acting only exists when you do it. And you do it for an audience. And it’s that. I mean, there are strangers sitting in the dark with strangers. Come on into the light and the energy goes from the light to the dark. And if you’re fortunate, it comes back to the light reinforced. And if it really, really works — and I’ve experienced this — you do create a circle of energy, which for me, of course, is an ideal model of an ideal society. But that’s what it’s about.

[33:00] Sinéad Burke: It’s that circle of energy tangible?

[33:03] Glenda Jackson: Oh, absolutely.

[33:04] Sinéad Burke: What does it feel like?

[33:04] Glenda Jackson: It feels as though it’s partly the energy, obviously of the play itself, but of an audience’s attention, concentration. You are believable to them. The play plays you, in an extraordinary kind of way. It is a truly unique experience. And I think it’s unique for the audience as well. It’s not just unique for the actors.

[33:27] Sinéad Burke: Has there been a moment at the end of a play, or at the end of a project, when that circle of energy has been at its most heightened? Can you remember it?

[33:36] Glenda Jackson: Not really, because if I take something from the play home, I haven’t done my job properly. I mean, everything should have been done on that stage. On that empty space. So, no. I mean, and one of the things I found quite interesting over the years is people say to me quite often, ‘how did you learn those words and you remember them?’ I don’t know. I’m just blessed in that way that I can and do. But once a project is over, be it well, plays the most obvious because it’s the one you do most often other than film and television — I can’t remember word the day after.

[34:40] Sinéad Burke: Really?

[33:41] Glenda Jackson: I can’t remember a word. It’s all gone. That might be my brain just decaying. But there you go.

[34:20] Sinéad Burke: You spoke earlier the fact that as you age, you have this understanding that you’re going back to your 15 and 16 year old self in many ways, or you feel that internally, perhaps more. But what would you say to 15 or 16 year old Glenda if you had the opportunity? Or is there anything you would advise them on or encourage them to do?

[34:43] Glenda Jackson: I was pretty good at school until I hit my teens, and I think it’s when all those, you know, whatever they’re called, start coursing through your veins. And I didn’t spend as much time learning as I could’ve done. For example, one of the big jokes in my form when I was about 14 or 15 — and tended always to be me that was chosen to participate here — there were cupboards in the classroom. Those removable shelves. And so the shelves would be removed and I would be locked in the cupboard, which the rest of the class all knew. This was a punishment for teachers we didn’t particularly like. And there I was incarcerated in the cupboard, and it was my job to tap mysteriously at certain moments during the class. I mean, really, how pathetic can you get? In some ways I wish — because as I said, now I am my age. I realize how little I know. That I perhaps had spent more time actually learning at school than I did.

[35:49] Sinéad Burke: What would you like to know then that you don’t?

[35:51] Glenda Jackson: Pretty much everything. I really would. I mean, there’s so many — I don’t, for example, understand artificial intelligence. My landline went out and my family insisted that I get a cell phone because the people who repair your landlines are very slow in doing the job. So I got this cell phone and I pretty much knew how to make a call on it. I couldn’t get incoming calls. I couldn’t. I didn’t know which button I pressed. So I said to my grandson, who at the time was 7 years old, he’s now 12. I said him, would you be good enough, I said, just to show me, because I didn’t know how to get an incoming call. He said to me, I’ve shown you how to do this three times. I am not doing it again. That puts you in your place, doesn’t it?

[36:38] Sinéad Burke: We spoke about earlier about that feeling of sometimes being alone. And had the Internet and technology can unite us in a way. And I’m conscious that this podcast is going into people’s ears in probably quite an isolated fashion. We have an audience of one in front of us. And many people, I think, and me, too, will be listening to you and saying, you know, you’ve had such bravery and confidence in using your own voice and in stepping forward for issues, or for characters, or for other people, and for yourself. Is there any advice or anything that you would say to people who are perhaps listening to this and thinking, I don’t know how. I don’t know if I can. I don’t know if I should.

[37:15] Glenda Jackson: They’re very, very difficult questions that if they are asking themselves that. I don’t where one would begin to do this. But experience is out there as others have experienced it, you know what I mean? And so you can tap into that. But I don’t feel that anything I’ve done is particularly brave, or outside the norm in a sense. Partly because — well, this is my theory. Partly because I was raised by women. I mean, I was born in 1936. You know, all the men in my family were away at war for those six years. I was raised by my mum and my aunts and my grandmas. And they also, apart from raising children, ran the country, didn’t they? And as happened in the first World War, where there had been an exactly similar situation — except at the end of that there were more than a million men who didn’t come home. Those women who’d run the country, run the families, done everything were patted on the head and told, thank you very much. Now go away, go back home. Do the cooking, the cleaning. And I think partly by what it happened after the First World War — well, I mean, we got the vote eventually, didn’t we, in the United Kingdom. And partly of the reaction after the Second World War, those generations weren’t prepared to just go away and get on with it. And I think that sort of fed into me, and that was something very much that I value. I mean, life had dealt all the women in my family fairly ropey cards, but they all had a sense of humor. They strongly believed in not crying over spilt milk. That, you know, life was there to be lived. So get on, do it and don’t moan. And those were very valuable and beneficial lessons.

[39:13] Sinéad Burke: So tenacity and confidence.

[39:16] Glenda Jackson: I don’t know so much confidence. I mean, just do it, I think.

[39:22] Sinéad Burke: And speaking of just doing it, we’re sitting here. We are reimagining, boldly, this society that we want to build and live in. What’s the one thing you want to see?

[39:33] Glenda Jackson: I would just like to see the acknowledgment of — this is paradoxical, I know this. We are uniquely individual. Every single one of us on the face of this earth. But we have so much to share if only we could. And we should. And let’s hope we will.

[39:52] Sinéad Burke: Glenda Jackson, it has been the most extraordinary privilege to sit across from you this afternoon. To learn from you and laugh with you and to hopefully instill inspiration and some ideas to those who are listening. Thank you so much for being on As Me today. It’s been an honor.

[40:08] Glenda Jackson: It’s been a real pleasure to meet you.

[40:13] Sinéad Burke: OK. If I’m honest, that was one of the very first As Me episodes that I ever recorded. I was so nervous. Literally, you could see my hands shaking on the table. But I hope that didn’t come through to you. Thank you, Glenda, for sharing yourself with us. This week’s Someone You Should Know is also an actress. But like me, she’s a little person. Her name is Fran Mills, and she is extraordinary in so many ways. But you might be familiar with her work because she’s currently starring in Harlots on Hulu. I’ve admired Fran’s work for such a long time. And she’s really challenging the parts that people can play when they’re born into specific types of bodies. If you’re not already following Fran, go do so immediately. On Instagram, she’s @frannnmills.

[41:04] Sinéad Burke: As Me with Sinéad is a Lemonada Media original and is executive produced by Jessica Cordova Kramer. Assistant produced by Claire Jones and edited by Ivan Kuraev. Music is by Jerome Rankin. Our sales and distribution partners, Westwood One. If you’ve liked what you’ve heard, don’t be shy. Tell your friends or listen and subscribe on Apple, Stitcher, Spotify or wherever you like to listen, and write and review as well. To continue the conversation, find me on Instagram and Twitter @thesineadburke and find Lemonada Media on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook @LemonadaMedia.